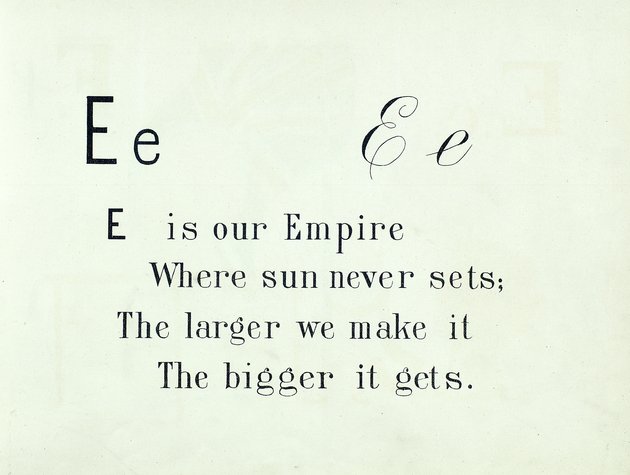

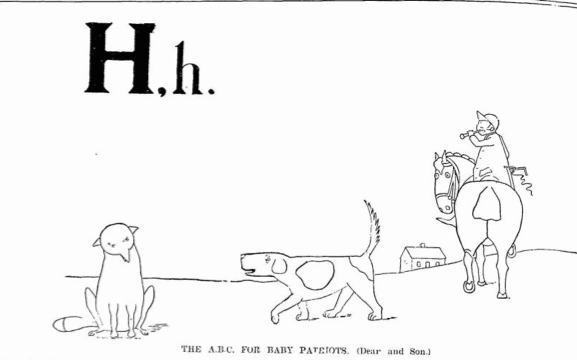

The cover image for this blog is taken from Mrs Ernest Ames’ ABC for Baby Patriots, an illustrated children’s book published in London in 1898. Packed full of jingoistic cartoons and imperialist rhymes designed to divert and delight the children of Britain and Empire, ABC for Baby Patriots is an iconic example of nineteenth-century imperial literature, and demonstrates in short order the ideas of Empire that were common in the Victorian era. As waves of imperial nostalgia crash against a British public beleaguered by Brexit debates and delusions, examining the commonly held fictions of Empire and imperial dominance is a timely project. The Empire of Nostalgia that we experience today is built upon the edifice of imperialism’s self-image (rather than the realities of Empire), and children’s literature encapsulates complex social ideas in easily digestible ways. As a source, therefore, it cuts to the quick of history and memory, national/imperial self-perception and indeed the social reproduction of ideas. As Antionette Burton has written in the introduction to her self-styled queering of the genre in An ABC of Queen Victoria’s Empire, ‘Mrs Ames ABC was an imperial orientation device’, designed to socialise children into an imperial world-view. The readers themselves, meanwhile, were positioned and affirmed as the rightful heirs to ‘our Empire / Where sun never sets; / The larger we make it / The bigger it gets’.

‘There is something very characteristic in the indifference which we show towards this mighty phenomenon of the diffusion of our race and the expansion of our state. We seem, as it were, to have conquered and peopled half the world in a fit of absence of mind.’

Here the same exculpatory idea is expressed in short order: ‘The larger we make it / The bigger it gets.’

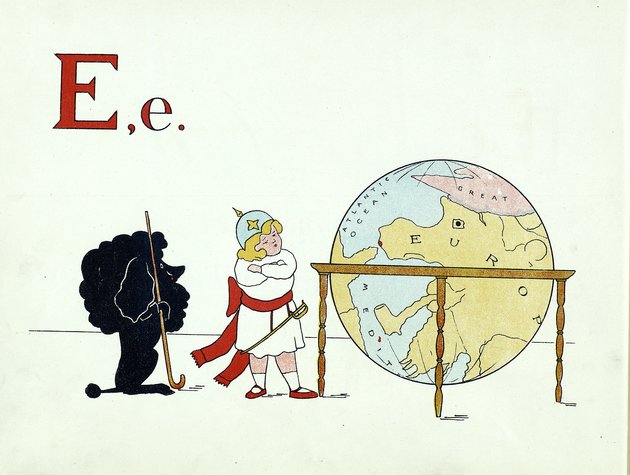

An interesting side-note, meanwhile, while Antionette Burton has asserted the figure here is a girl, having cross-referenced with Ames’ other picture-books, and taking into consideration the tradition of keeping young boys in dresses and curls until they were ‘breeched’ around the age of seven (not to mention that in this time period red was the more common colour for boys, and blue for girls), it seems more likely to me that he is a boy, learning how to rule over his ‘natural domain’– the British Empire.

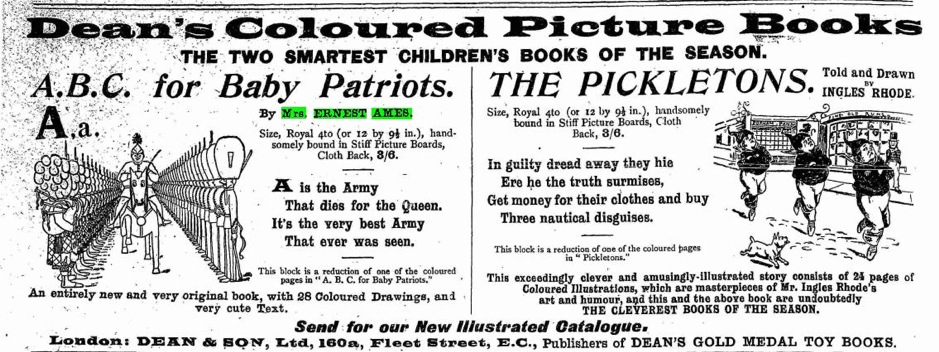

Surprisingly little is known about Mrs Ernest Ames – the name under which she published. Born Mary Frances Leslie-Miller in 1853, we do know that she published numerous children’s books, many jingoistic in flavour, at the turn of the twentieth century and at the height of the Boer War when the appetite for imperial children’s literature was strong. Some she wrote herself (including An ABC, for Baby Patriots and Wonderful England!: Or, The Happy Land in 1902), others her husband wrote and she illustrated (including Really and Truly! Or, the Century for Babes in 1899 and The Tremendous Twins or How the Boers Were Beaten in 1900). She became engaged to Ernest Fitzroy Ames in 1894,[1]and was presented to the Queen ‘on her marriage’ in 1895, suggesting a rather late attachment at the age of 42.[2]She joined the Ladies’ Grand Council of the Primrose League (a Conservative pressure group founded in 1883 and named after Benjamin Disraeli’s favourite flower) in 1896, and came to fame through the publication of her ABC, ‘in which each letter is made to stand for an idea connected with the Empire’, in time for Christmas, 1898.[3] The book was generally well-received, although the Daily News noted for its readers that it was ‘of course… Chauvinist in tone.’[4] The first stanza was widely advertised, with illustrations, and certainly confirmed this characterisation.

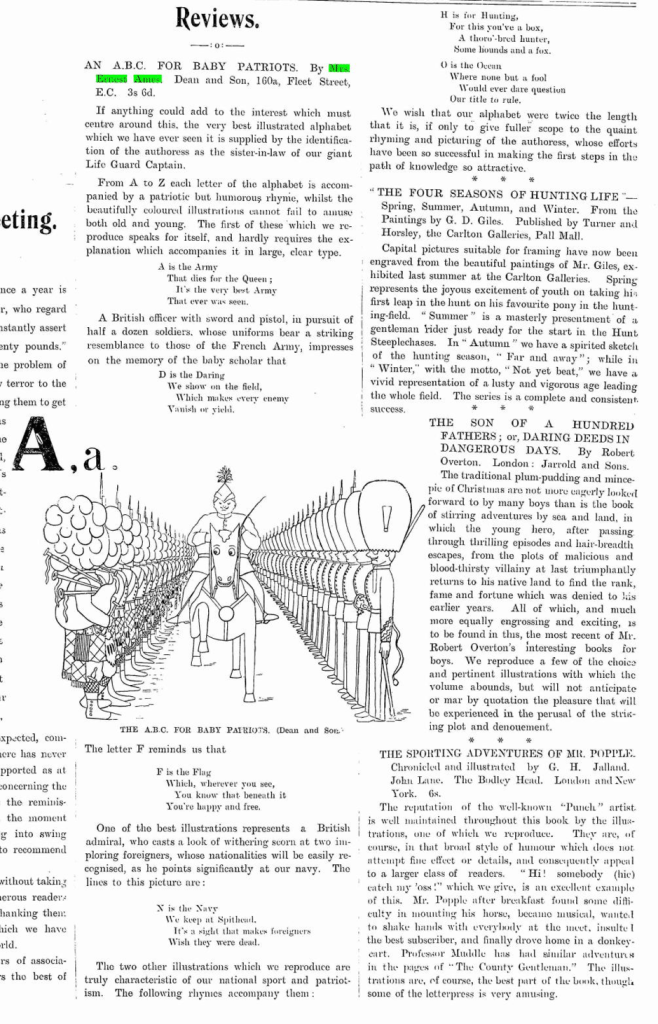

Filled with ‘amusing rhymes and 24 large coloured comic picture pages’, the book was priced at 3s. 6d.[5] While this was by no means affordable for all, it was on the cheaper end of Dean & Son’s publication list (other children’s titles being as much as 7s. 6d in the same year). The County Gentleman: Sporting Gazette, Agricultural Journal, and “The Man about Town” devoted a significant review to the children’s chapbook, citing not only its ‘patriotic but humorous’ tone as something to raise its attention, but also the fact that its author was ‘the sister-in-law of our giant Life Guard Captain’ Oswald Ames (who at 6 feet 8 ¾ inches led the Queen’s procession to St Paul’s Cathedral for the Diamond Jubilee Service on 22 June 1897).[6] They reproduced three of the illustrations and four of the rhymes, speaking to the values of the esteemed publication.[7]

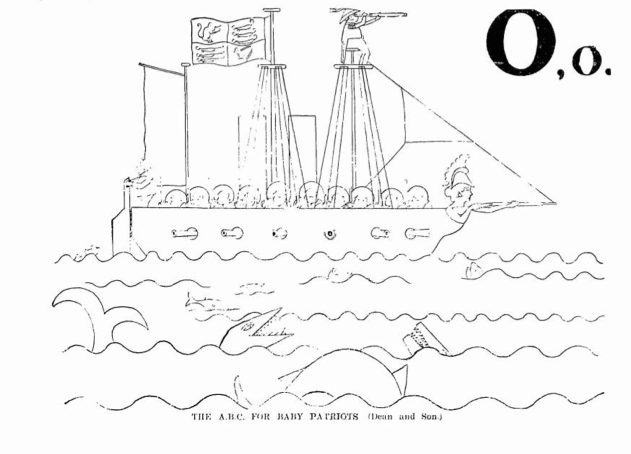

By December 1899 a new edition had been published, and Dean & Son’s advertisements were claiming that ‘the book bids fair to be the most successful gift book of modern times.’ While the publisher continued to reproduce the image of ‘A is for Army’ in their adverts, the text reproduced was now ‘N is the Navy / We keep at Spithead, / It’s a sight that makes foreigners / Wish they were dead.’[8]

Why, then, reproduce this colonial imagery in this blog? Firstly, as a blog about teaching the history of Empire it cannot be denied that this is a useful source with which to engage students. Vibrant and clear, it demonstrates imperial ideologies in their simplest form, allowing students to confront the ways in which Empire was recognisable enough to form a staple of children’s literature, while at the same time giving them space to critique the imperial imagery on the page. The publication date of this book is also significant. As we have seen above, it was published just a year before the outbreak of the Second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) and the Ameses quickly followed its publication with The Tremendous Twins or How the Boers Were Beaten(somewhat prematurely) in 1900. As Kathryn Castle has argued, this was right at the apex of imperial publishing for juvenile audiences (1880-1914) which worked to ‘fashion an Empire for the young.’[9] This was the generation that saw Britain and its Empire through to the 1950s and 60s – a jarring age of decolonisation for generations brought up on imperial propaganda.

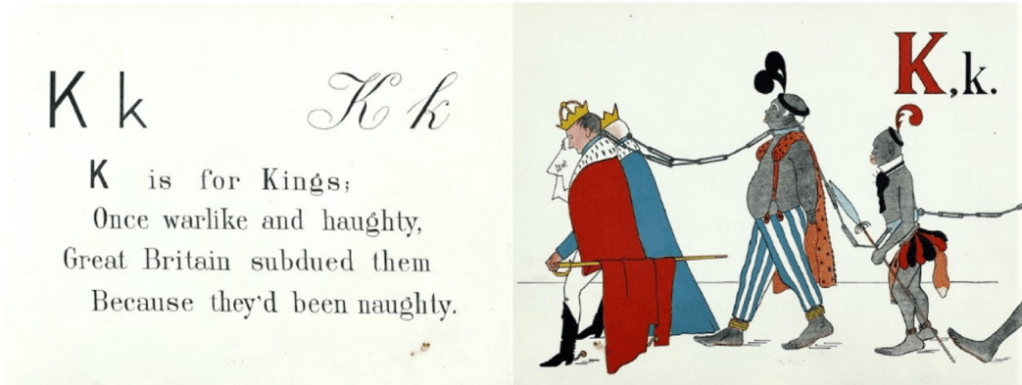

Intriguingly, meanwhile, a recent article by Megan A. Norcia suggests that the imperial content of ABC for Baby Patriots has been exaggerated, and that it can in fact be read as ‘a ruthless satire on overweening nationalism and imperial greed, written as much for adults as for children.’[10] While I am not entirely sold on that argument, either way it cannot be underestimated the effect such imagery as the below would have had on a young audience even if adult readers were scoffing into their beards and bonnets. The ways in which its pages align with imperial memes of Britishness, from power to honour to even the intricacies of constitutional monarchy (see K is for Kings), speak to the prevalence of those ideas even at the same time as they may have been satirised within its pages. As Norcia concludes,

Ames’s picture book is situated at a fascinating nexus of imperial ideology, political satire, and alphabetic instruction, and it begs for another look from scholars at the way in which it presents a subtle, sophisticated critique of the very imperial ideology that it has so long been charged with promoting. Baby Patriots is a visual and literary artefact freighted with cultural importance, showing how Victorians viewed their children, their empire, and their role in the world.[11]

Dr Emily Manktelow

(Royal Holloway, University of London)

[1] TOWN AND COUNTRY GOSSIP.

Horse and Hound: A Journal of Sport and Agriculture (London, England), Saturday, December 08, 1894; pg. 775; Issue 559. New Readerships

[2] THE QUEEN’S DRAWING ROOM .

The Morning Post (London, England), Wednesday, March 06, 1895; pg. 5; Issue 38295. British Library Newspapers, Part II: 1800-1900

[3] CHILDREN’S BOOKS .

The Morning Post (London, England), Thursday, December 08, 1898; pg. 3; Issue 39472. British Library Newspapers, Part II: 1800-1900.

[4] BOOKS FOR YOUNG READERS .

Daily News (London, England), Friday, December 2, 1898; Issue 16439. British Library Newspapers, Part I: 1800-1900

[5] Multiple Advertisements and Notices .

The Morning Post (London, England), Monday, December 12, 1898; pg. 9; Issue 39475. British Library Newspapers, Part II: 1800-1900.

[6] https://www.rct.uk/collection/2930983/captain-oswald-ames-1862-1927-2nd-life-guards

[7] The County Gentleman: Sporting Gazette, Agricultural Journal, and “The Man about Town” (London, England), Saturday, December 24, 1898; pg. i; Issue 1911. New Readerships.

[8] DEAN’S RENOWNED CHILDREN’S BOOKS.

Myra’s Journal (London, England), Friday, December 01, 1899; pg. 50; Issue 12. New Readerships.

[9] Kathryn Castle, Britannia’s Children : Reading Colonialism through Children’s Books and Magazines (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996), p. 6.

[10] Megan A. Norcia, ‘”E” Is for Empire?: Challenging the Imperial Legacy of An ABC for Baby Patriots (1899)’, Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 42(2) (2017), 125-148. Citation on p. 126.

[11] Megan A. Norcia, ‘”E” Is for Empire?: Challenging the Imperial Legacy of An ABC for Baby Patriots (1899)’, Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 42(2) (2017), 125-148. Citation on p. 143.

Leave a comment