Lily Ann Lofty examines the role of religious satire in the uncomfortable imagery of her family’s colonial past.

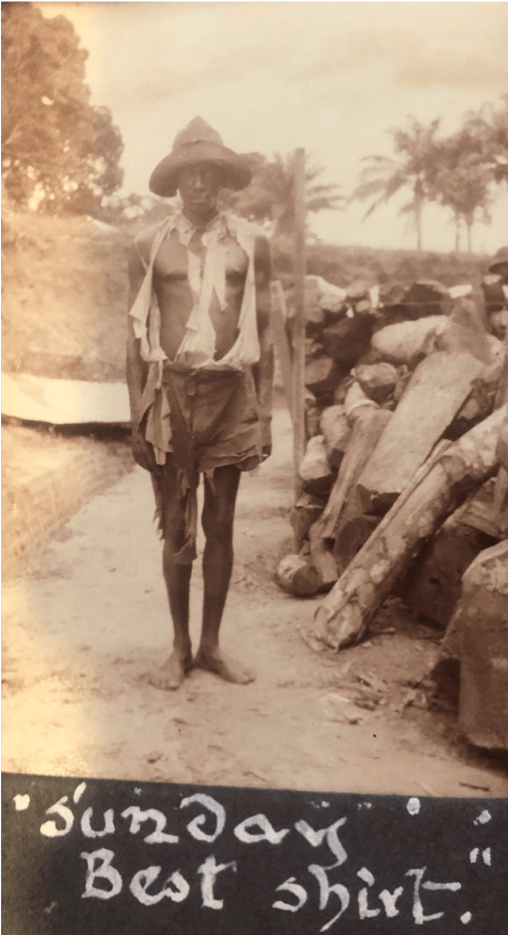

My family history is what prompted me to study History at university and therefore I have consistently investigated my family’s past, particularly into the imperial ties that it holds. My grandfather, Hilary Lofty, I have learnt a significant amount about since pursuing my specialist studies into British imperialism. My grandfather from when he was young was fascinated by ‘exotic’ countries and spent his life pursuing employment in Africa. After he had spent time as a marine in Sierra Leone and travelling the Congo, he decided to act on his love for Africa and relocate his British family to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). The photographs he took in the Congo fascinated me on many different levels, but most of all they highlighted his British identity being exemplified in the countries that he enjoyed working and travelling in. ‘Sunday Best Shirt’ is the caption my grandfather chose to use to depict this photograph he took of a Congolese man in the Belgian city of Kinshasa, previously known as Leopoldville. My grandfather left Britain for the Belgian Congo in 1924 with Huileries du Congo Belge, a subsidiary of Lever Brothers, which would then become Unilever, to aid the organisation of extracting palm oil from the west of the African country. The photographs he took in Kinshasa are constructed in an album with varying captions, however this photograph is particularly compelling in suggesting the purposes of the album and how it can be related to the aftermath of the height of European imperialism and specifically the influence of religion in forming British identities in comparison to the indigenous ‘other’.

The use of the well-known British phrase ‘Sunday Best’ illustrates a form of amateur religious satire, as it describes an extremely malnourished man in a dishevelled background, with the added symbol of exoticism as palm trees in the scenery. The use of the expression immediately sets a precedent of difference in identities between the Congolese man and my British grandfather. The satire highlights the torn, yet western, clothes whilst using a common British phrase to exemplify how the man would not have the choice to wear his ‘Sunday Best Shirt’. The primary source highlights the significance of the caption to the whole piece. Instead of the photograph simply providing evidence of his first visit to an African country to show to his family back in the metropole, my grandfather is engaging with the racial and religious divides between his British identity and indigenous Congolese culture, subconsciously or not.

Religious satire, particularly written by a man whose profession is not satirical entertainment, contributes to a much wider debate on British imperialism between the Cambridge scholars who argue that British imperialism was a purely economic driven system, and Manchester scholars who argue that an imperialist culture existed in Britain. This source contributes to the Manchester School of thought’s argument whereby Britain not only was led by an imperialist society in the mother country, but that British society consciously interacted with colonialism throughout the nineteenth century.[1] Therefore, religious satire provides crucial evidence to exemplify how even after the height of the British Empire in the twentieth century, business men in the Congo (such as my grandfather) were using comical phrases to create a distinction between themselves and the indigenous ‘other’. My grandfather was influenced by an important legacy of the British Empire, that a clear distinction between white, British society and indigenous people in Africa, could be defined by not only their physical differences but culture and religion. Therefore, he could consciously provide comical entrainment from it with the view to making people laugh. To some audiences of the early twentieth century, the photograph may have caused paternalistic sympathy towards the man. However, from my grandfather’s perspective and as Dustin Griffin highlights in his Critical Reintroduction of Satire ‘a rhetorical performance of satire is designed to win the admiration of the audience’ and suggests that he probably consciously thought of the caption in order to receive some appreciation for the pun.[2]

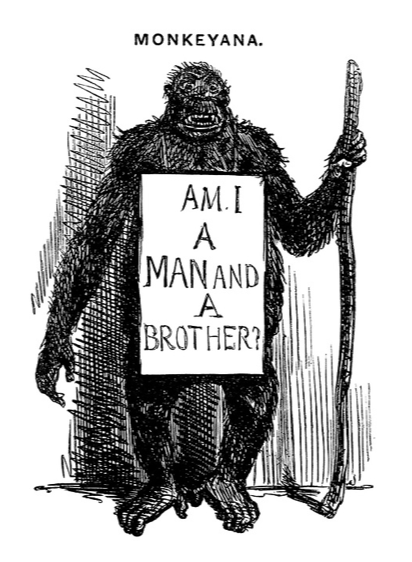

Religious satire was an influential part of Victorian culture as it was produced in a society that was becoming more doubtful of religious scripture to explain creation, and more aware of scientific theories. However, there was a prominent criticism of scientific explanations, particularly Darwin’s Theory of Evolution, which can be understood through analysis of satire. Simultaneously, much of this satire also tapped into discourses of difference between colonisers and the colonised. Particularly, satirical work on Evolution, often used the personification of an ape to highlight their perceived ridiculousness of the theory of apes evolving into humans. In one illustration that featured in the periodical Punch, an ape holds a sign questioning ‘Am I a Man and A Brother’, a play on words of a popular phrase used in the evangelical Anti-Slavery Campaign.[3]

The illustration mocks the Theory of Evolution, whilst using a common racial stereotype used in the nineteenth century, the comparison of a black person and an ape. The Anti-Slavery movement was a consistent topical point of conversation in the late eighteenth and nineteenth century and thus printed images in this period contributed to an ever-growing vocalised discourse.[4] This occurred in metropolitan society which was prompted by the press at the time, through the use of satire. Consequently, religious satire (professional or amateur) was a popular method in creating distinctiveness between racial groups in the British Empire, which Janet Browne highlights in her article ‘Darwin in Caricature’, by analysing how satire contributed to a popular culture in Victorian society.[5]

My grandfather’s use of satire clearly evidences a Victorian, imperial legacy. His comical comment not only reinforced his individual identity in the collective identity of what it meant to be British (in this example using religious puns), but in doing so provided the ideological separation between himself and an indigenous man that justified his role in British imperialism.

[1] Particularly the revisionist scholarly debates between John Mackenzie (Manchester School of Thought) and Bernard Porter (Cambridge School of Thought).

[2] Dustin Griffin, Satire: A Critical Reintroduction, (Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky, 1995), p. 71

[3] See the Punch historical archive, < https://www.punch.co.uk/index/G0000Uiv3S1UFh5o >

[4] Catherine Hall, Civilising subjects: metropole and colony in the English imagination, 1830-1867, (Oxford: Polity, 2002), p. 107

[5] Janet Browne, ‘Darwin in Caricature: A Study in the Popularisation and Dissemination of Evolution.’ Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 145:4, 2001, p. 509

Leave a comment