Deb Wood examines the role of pocket globes in teaching Britons how to rule an Empire.

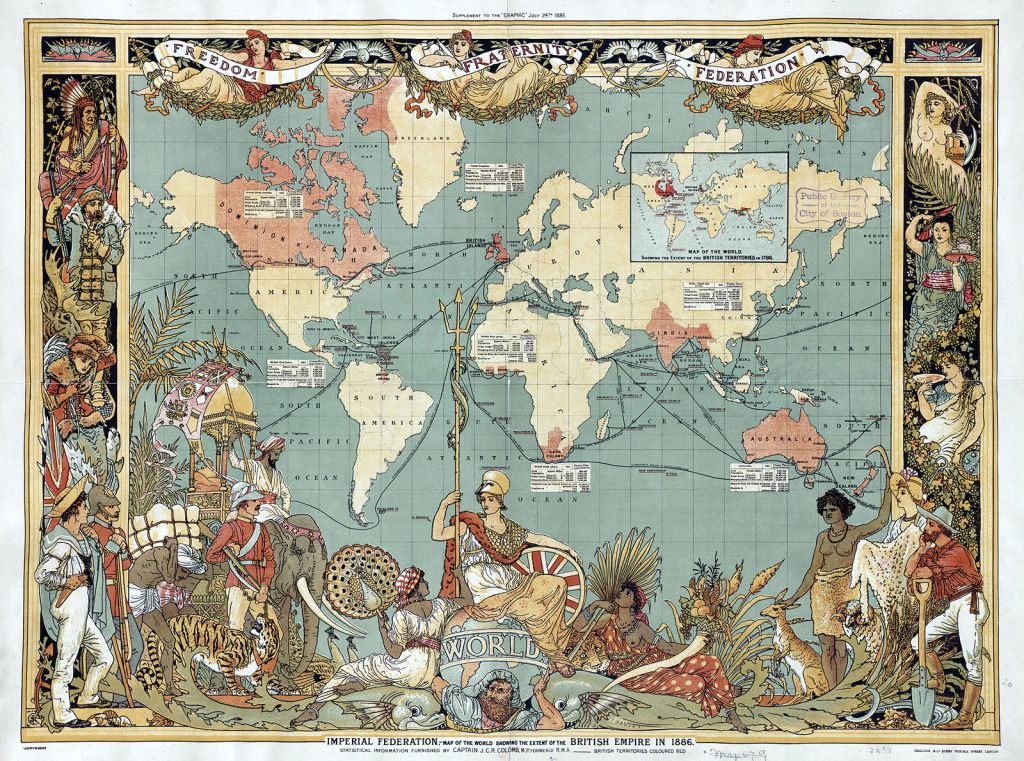

When we talk about mapping the British Empire, the image above is often one of the first to come to mind. With its swathes of red spreading across the map like a half-finished colouring book, this map takes a moment to recognise the Empire’s growth, and to highlight the conquering work that is still to be done. However, for an empire that spanned much of the globe and spilled across centuries, this single, two-dimensional image is far from the be-all and end-all for representing its influence.[1]

The National Maritime Museum’s collection of globes, like the empire, spans several centuries in a wide variety of forms, with an explosion in size throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries. But what can a globe add to the conversation when there are so many much more famous and accessible maps to hand? Well, as it turns out, these classy conversation-starter decorations are often laden with an undertone of imperialist thought, whether consciously or not.

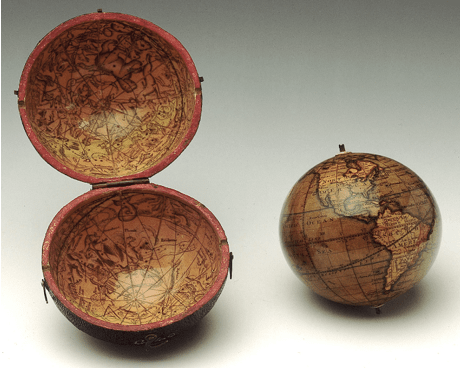

At first glance, this pocket globe looks like a somewhat cumbersome gimmick – after all, how small could they really get? In fact, this globe itself measures in diameter at about 7.5cm, (or approximately 3 inches to the imperially minded among us), with the celestial case adding a measly extra centimetre to the load. As well as being an interesting addition to the more standard pocket watch, this globe boasted the latest geographical knowledge from across disciplines, marking out globally ‘important’ features such as the monsoon-prone regions of India, the routes taken by key explorers like Cook, and of course, the Greenwich meridian.[2]

The connotations of keeping the world in your pocket have an undeniably imperialist twist. The idea of reducing the whole globe down to a handheld commodity made it easy for the owner to imagine themselves as owning a part of the great empire that belonged to their nation. By reducing the size this much, as well as the Mercator scale’s skewing of artistic perspective to enlarge the amount of the globe covered by Britain, these globes made the idea of further expansion seem much more feasible. After all, when the land that was waiting to be conquered was already in the palm of their hand, the job ahead began to look a whole lot more manageable.

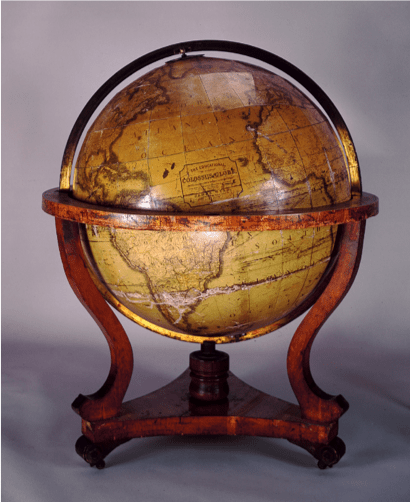

As the empire grew, so did the size of the globes. The National Maritime Museum’s collection suggests that pocket globes like the 1834 model above fell out of fashion by the end of the decade, as the larger table or floor sized globe began to take its place. Metaphorically speaking, these globes represent not only how much the Empire’s influence had grown, but also how much more weight it carried in the lives of Britons at home. As a household decoration, globes were certainly eye-catching – not only in size, but also in practicality, acting as a conversational aid for discussing travels both undertaken and read of, and more generally about the latest news from across the empire.

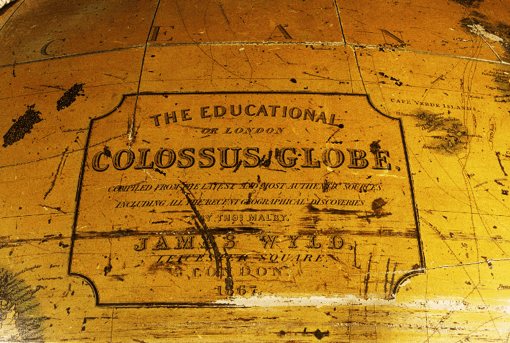

However, for this to work, the globe needed to be up to date. This particular globe, dating from 1867, declares its authenticity on a conveniently blank patch of the Atlantic. Having only used “the latest and most authentic sources”, the creator declares this globe to include “all the latest geographical discoveries” on its surface, reassuring its owner that, with this globe, they won’t be left behind when it comes to the latest developments. With a globe to spark conversation, the glories of an ever-expanding empire were brought not only to Britain, but also made their mark in the home.[3]

The globe’s title, “The Educational Colossus Globe”, is perhaps even more telling. Much like the jigsaw puzzles of the period, globes had a double purpose in the upper-middle class household; not only for entertaining adults, but also to educate their children into the ways of imperial thinking. From a young age, boys in particular were made aware of the conquests of the current generation, and also of the gaps that still remained on the imperial map. This sense of imperial responsibility was thus passed on to the next generation of politicians, governors, and explorers, preparing them from an early age to play their part in Britain’s imperial history.

So what can these globes tell us about their owners, and their place in Britain’s imperial history? They were both made decades earlier than the famous Imperial Federation Map, and thus their creators had to recognise that these models were somewhat temporary, and would be replaced as more discoveries were made, and new territories claimed under the Union Flag. The imperialist nature is far less blatant than the map’s – rather than marking out what has already been claimed in bold colours, the globes instead show a whole world of possibilities, guiding the eye onwards and upwards with snippets of information and references to previous, glorious achievements. It is impossible to know whether this imperially driven mindset was present when the owners of globes like these bought them, or whether they really hoped to indoctrinate their visitors and families alike into this way of thinking. Regardless of intention, however, the underlying imperialist tone in these globes is ever-present, giving everyday Brits a chance to own and show off their own understandings and representation of the phenomenon known as “their” ever-growing Empire.

[1] Walter Crane, The Imperial Federation: Map Showing the Extent of the British Empire in 1886, colour lithograph, first printed in The Graphic, 24th July 1886

[2] Terrestrial and celestial pocket globe, by John Adams, London, c. 1834. Held in the National Maritime Museum collection.

3 Terrestrial floor globe, by James Wyld II, London, 1867. Held in the National Maritime Museum collection.

4 ibid.

Leave a comment